In my eye line

"Kohl isn't a product, it's a cultural institution." Meet the author of Eyeliner - A Cultural History; and get important updates on Bangladesh and Myanmar.

Hello to you!

It started with a thought you might be interested in this book message from a friend back in December. My friend was right - not only was I interested, I was hooked. The book, Eyeliner by Zahra Hankir, asks its readers to 'eschew the Western gaze' and leave behind Eurocentric characterisations of a cultural practice that has existed for thousands of years. This is not 'a book about make-up'.

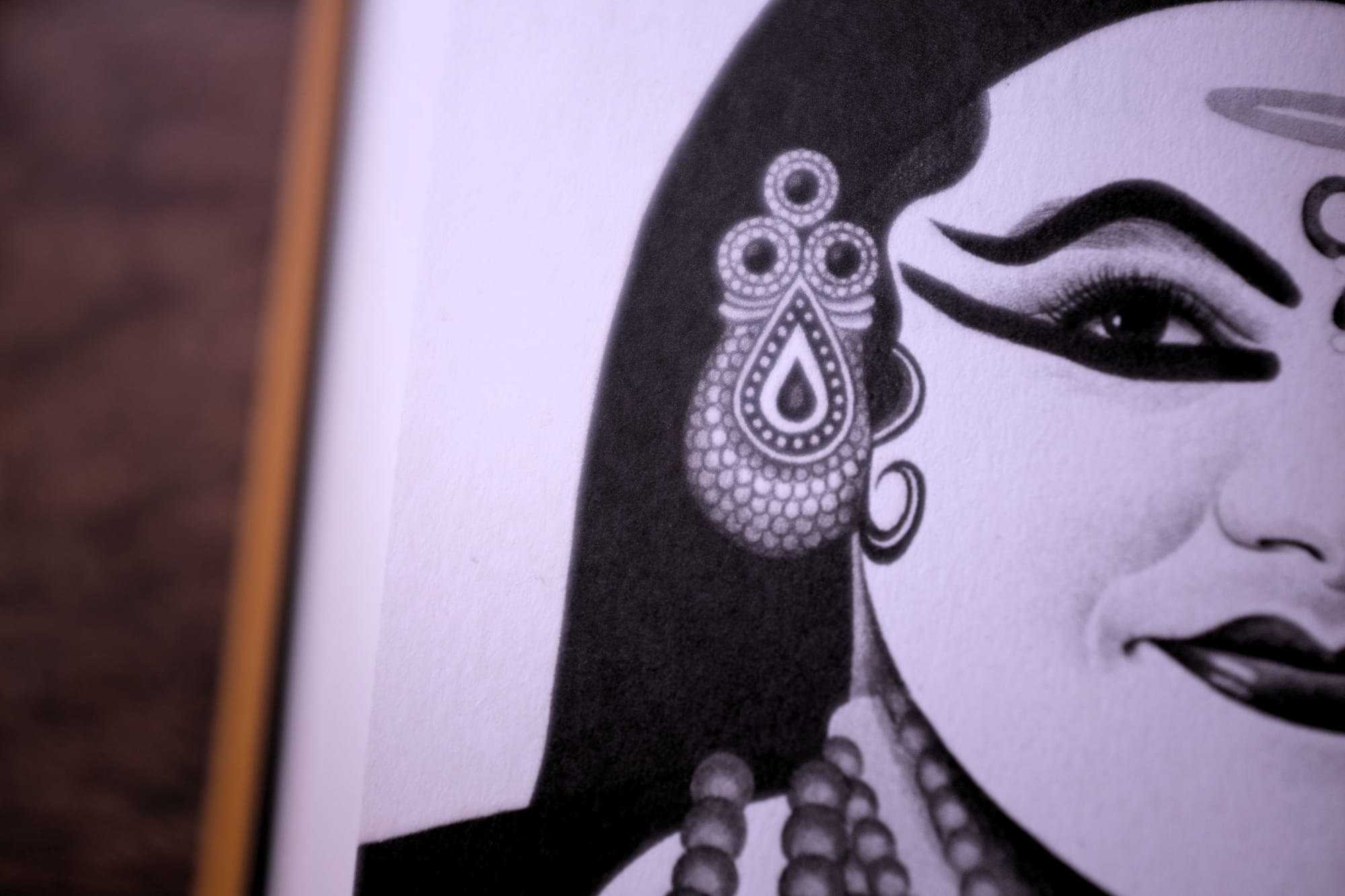

Within the pages of this book we visit Bedouin's in Jordan ("Kohl isn't a product, it's a cultural institution"), Wodaabe festivals in Chad, the protests for women's liberation in Iran and kathak dancers in Kerala amongst many others. Glimpsing into a world that includes drag performers, chola lowriders and the Egyptian feminist Nawal el-Saadawi who used her eyeliner pencil as a tool to continue writing while in prison.

Of course, I had to get in touch with Zahra Hankir in New York to see if she would like to talk about her book. I am so happy she said yes and the results of our emailed discussion is below.

Enjoy and see you on the other side for important updates on Bangladesh and Myanmar.

Eyewitness - a discussion with Zahra Hankir

Tansy: Despite having a huge impact on the world, topics like makeup (and fashion) are often wrongly dismissed as trivial. How do you account for this and how did you protect yourself against this line of thinking while writing this book?

Zahra: These are multi-billion dollar industries that we’re talking about – in that respect, we’ve already transcended the idea that makeup is trivial, as it says so much about human behaviour. I would also argue that eyeliner isn't just "makeup": There is far more to the cosmetic than meets the eye (sorry, not sorry). Eyeliner application isn't a frivolous occupation that solely relates to aesthetics: it represents a profound cultural and historical lineage that has shaped, and been shaped by, societal norms and individual identities throughout history, especially in the non-Western world and among communities of colour and other minorities.

This perspective challenges the conventional dismissal of makeup (and, by extension, fashion) as trivial by highlighting their roles as tools of expression, empowerment, and even resistance. Eyeliner is even more distinguished than many other cosmetics due to its multifaceted role, as it sits comfortably at the nexus of power, gender, beauty, race, religion, spirituality, ethnicity, heritage, identity and science.

In writing this book, I actively sought to elevate the narrative around eyeliner from mere cosmetic to a cultural artefact, intertwining personal stories with historical context to demonstrate its significance. It wasn't hard to explain the deeper meanings and impacts that this seemingly frivolous object has had on broader cultural and social dynamics: there were countless stories every which way, from the subway to the deserts.

My mother's encouragement reminded me that telling stories centred around pride and joy in our culture is just as important as exploring narratives of pain and suffering. This became especially important in the aftermath of the Beirut blast in 2020, during the pandemic, and more recently amid Israel's bombardment of Gaza.

Tansy: I admire how you have taken the cultural practise of applying eyeliner and used it as a lens to show people a fresh view of the world. Much of the book is set in South West Asia and North Africa – a vastly exploited region which is currently on fire with the relentless brutality of Israel against Gaza and Palestinians. Would you agree there are lessons in the book regarding imperialism, how it is resisted, and what would make for a better future?

Zahra: Inevitably, in doing this research, I dealt with communities and cultures that had experienced the fallout from colonialism and imperialism and to whom kohl and kohl-making carry immense value. In many ways, this is a deeply political object. Consider the situation in Gaza today, which has been subject to a form of cultural erasure by Israeli military forces. Amidst the war, within the Palestinian context, maintaining traditions like kohl-making carries added importance. The tradition of kohl consequently serves as a profound link to Palestinian cultural heritage and by extension the larger historical narrative of the region. In that light, the continued wearing of kohl stands as a testament to the endurance of culture — serving, in a way, as an act of cultural preservation and even resistance.

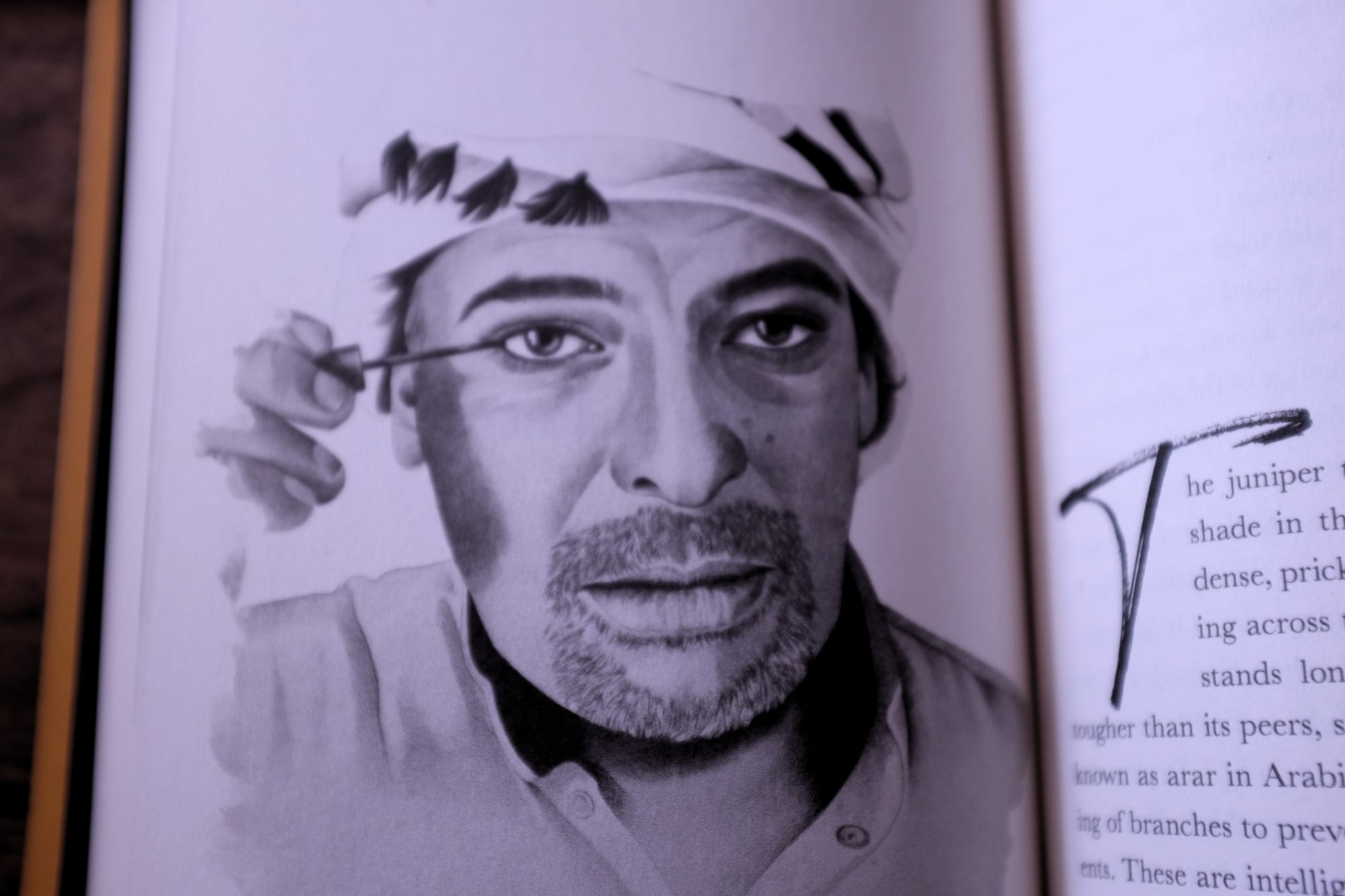

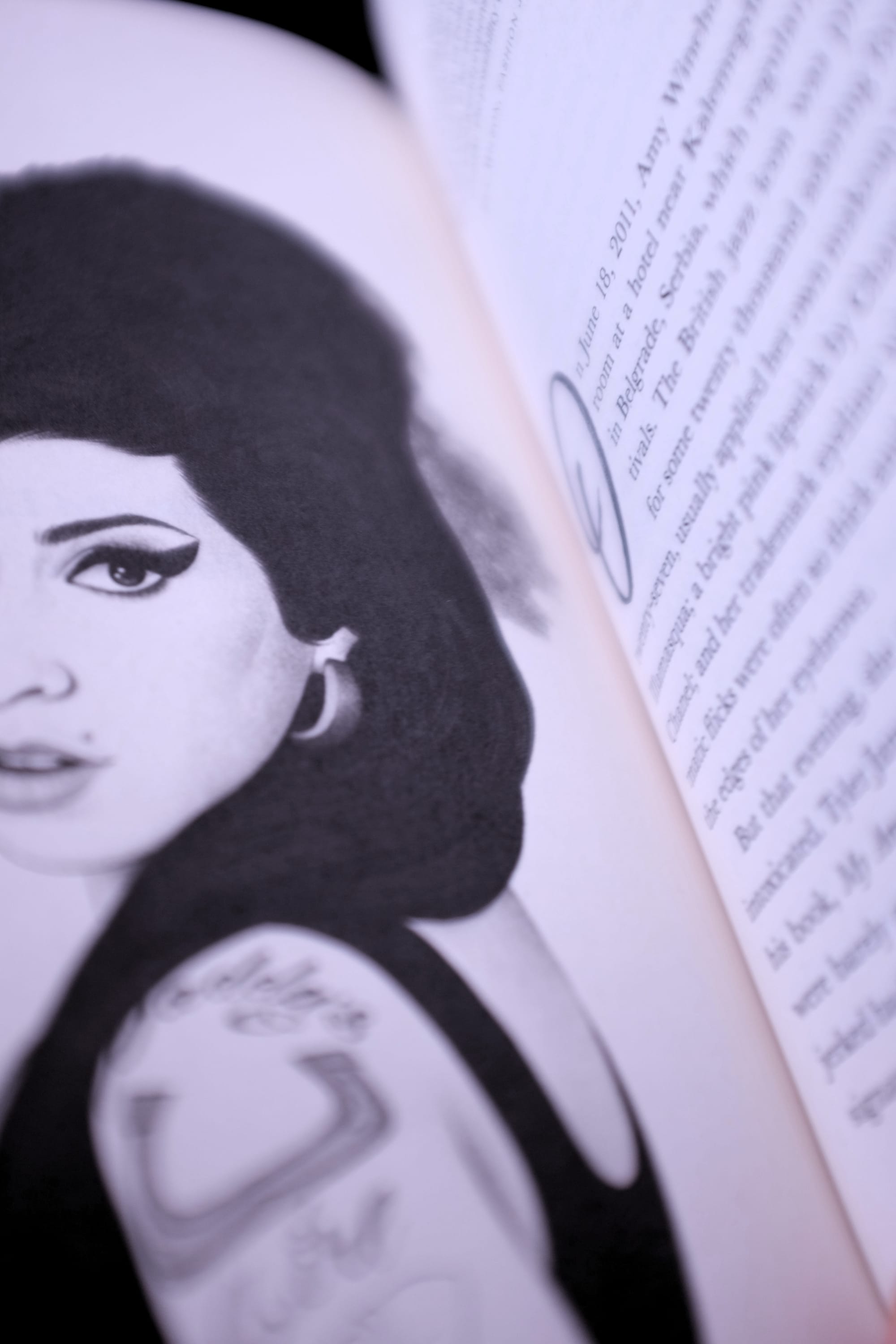

Beautiful illustrations by Mercedes deBellard

Tansy: Eyeliner is a rich, well researched book, so much so that I kept finding myself wishing "time travel journalism" was possible so you could have gone back in time to meet some of the people and see some of the events you've written about. Is there a time you'd like to travel back to?

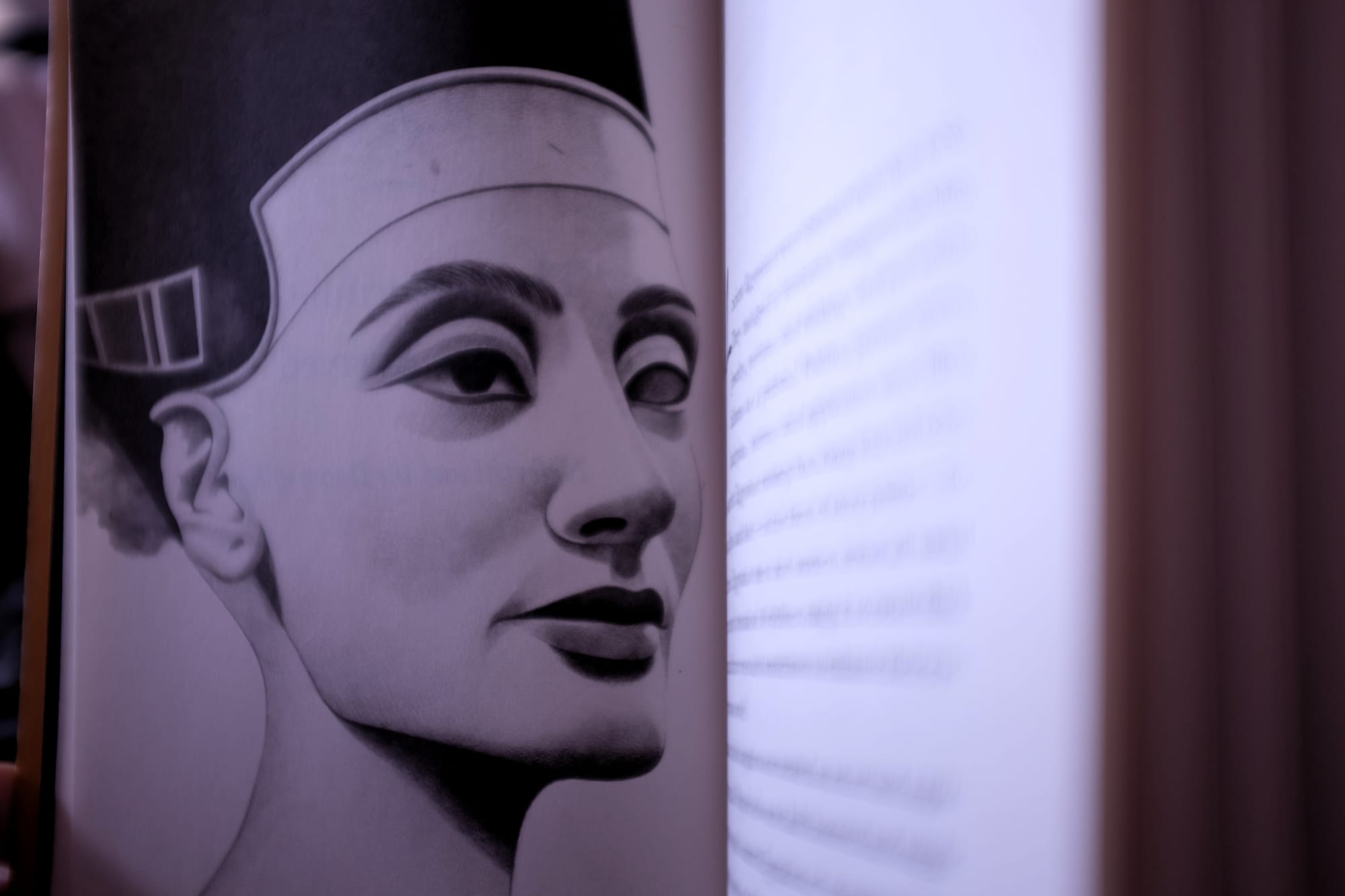

Zahra: Hands down, no questions about it – I'd travel to Ancient Egypt, specifically around 1370 BCE, to meet Nefertiti, the queen of all queens. The period during which she reigned was one of profound cultural and religious change in Egypt, with revolutionary artistic and societal shifts. Nefertiti navigated her role alongside her husband, the Pharaoh Akhenaten, with great power, influence, and, of course, style. Ancient Egyptians were obsessed with their looks in the best of ways, and Nefertiti was a distinct embodiment of that obsession. We've come to know Nefertiti through her bust, and one of the most distinctive features of her look was her eyeliner, which lends her a regal, somewhat androgynous energy. Using kohl in ancient Egypt wasn't just cosmetic — it symbolized political power, spiritual devotion and personal identity. It also protected against the evil eye, guarded against the sun's glare, and treated the eyes medicinally.

Despite being centuries apart, the pigment's composition, use and application across vast areas of the global south today overlap with how kohl was used in Ancient Egypt. In my book, I quote the author Judika Illes as saying: "An ancient Egyptian woman time-traveling to the present would surely find much to puzzle her, but hand her a modern kohl container and stick and she would know exactly what to do with it." (I'd be tempted to take some NYX graphic liners back in time with me. Though I'd imagine the Ancient Egyptians wouldn't be too keen on highly processed eyeliners, given they made theirs from naturally occurring materials.)

Tansy: I’m grimly aware of Britain’s role in cultural theft, but before I read Eyeliner I did not know the iconic 3,400 year old bust of Queen Nefertiti has been in Germany since 1913.

Zahra: Egyptians are leading an ongoing effort to bring Nefertiti home. Astoundingly, one typical response from the Germans, at least according to the Egyptian archaeologist Zahi Hawass, has been that the Egyptians would not be able to keep her safe. Again, this is an extension of colonial and orientalist mindsets that need to shift – the same ones that facilitated the theft of the objects in the first place.

The story of Nefertiti’s bust brings to light the bigger picture of how historical treasures have been moved, taken, or stolen from their homelands. It's a rough part of the history of colonized nations. And the issue needs to be taken more seriously in the geopolitical landscape, especially considering Britain and other Western countries' role in removing these cultural items and then stubbornly holding onto them despite ongoing repatriation efforts. (Sidenote: it was such a bizarre moment of my research to travel to Germany from the MENA region to see Nefertiti's bust in person.)

As for what should be done to bring these artefacts home – international cooperation and legal frameworks, including UNESCO conventions, should be strengthened and more widely adopted. In the interim, museums and institutions holding onto these precious objects should adopt more transparent practices about repatriation efforts and engage in good-faith partnerships with source countries, including loans or shared custodianship arrangements.

Tansy: Is there a favourite line from Eyeliner that you would like to share with us?

Zahra: One of my favourite parts of my book research was speaking to people about the history of eyeliner and their memories of it – and coming across what my editor liked to call "sticky" or “memorable” details. One of those was this anecdote, which my mother shared with me: In the Arab world, if someone asks about a person who's been dead for a long while, the respondent says of the deceased that they've been underground for so long, their "bones have become kohl applicators."

It translates differently, of course, and it sounds rather grim, but it also has a poetic depth that resonates profoundly with me. In some ways the saying reflects how the cosmetic has been woven into the fabric of life and death. And it’s something of a reminder of the transient nature of human existence and the lasting impact of our cultural practices. I find this blend of the personal with the universal, and the mundane with the profound, particularly moving and symbolic of the themes contained throughout my book.

- Zahra Hankir is a Lebanese-British journalist who writes about the intersection of politics, culture, and society. Her first book Our Women on the Ground is a collection of essays by Arab women journalists. Eyeliner is out now.

Notes From The Profit Margins

These are some of the things I am keeping my eye on in the industry right now.

- The Rana Plaza Solidarity Collective is back and holding a protest walking tour in London on the 24th April, meeting 17:45 at Soho Square.

What would your manager say if you asked for a pay-rise? Would they sack you for asking and have you beaten by hired thugs? Would they do everything they could to smash your trade union? Would they work with the government to criminalise your entire sector? Would they issue unnamed arrest warrants so that everyone in your workplace was constantly afraid of being called a criminal and put on trial? Would you be shot dead on the street?

If this sounds unfair, join us to stand in solidarity with Bangladeshi garment workers who are facing unprecedented attacks on their workplace freedoms and civil liberties:

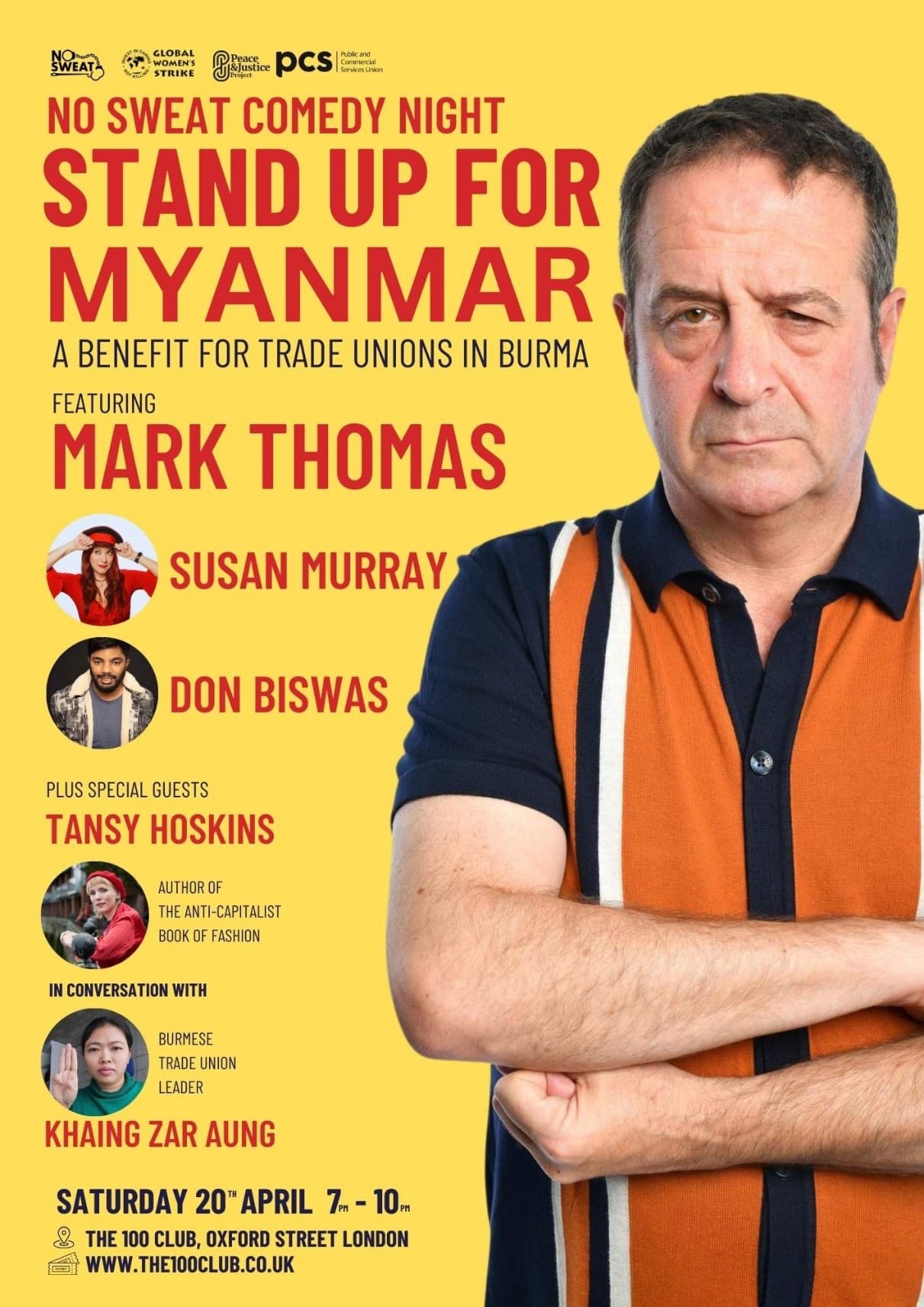

- Two excellent events on Myanmar in London on 20th April. I'm interviewing Burmese Trade Union Leader Khaing Zar Aung at The 100 Club: https://linktr.ee/myanmarconference2024

- Two very important pieces on how to stop gender based violence in factories from Thivya Rakini the leader of the TTCU (Tamil Nadu Textile and Common Labour Union). It's vital to listen to the people who are ALREADY DOING THE THING!

2) Why is the sexual harassment committee (IC) failing in your garment supplier factory?

- New Asia Floor Wage Alliance (AFWA) report about informally employed workers who are employed within formal workplaces like factories. Typically informal employment without a proper contract is characterised by unspecified wages, hours or conditions, and being at the mercy of whomever has 'employed' you - from sleazy managers to the corporate fashion brand at the top of the food chain. Highlighting how much factories rely on informal employment challenges binary distinctions between the informal and formal sectors. The report is called THREADED INSECURITY and is very much worth checking out.

- I found this article on #Shein very interesting - esp. on the intersection of slash fashion and Facebook: 'To promote its fire hose of new products, Shein and its competitors spend lavishly on Facebook and Google ads (so much so that Shein and Temu ad spending is partially responsible for Meta’s recent revenue increase).'

- And finally... a poignant story on crafters completing the unfinished blankets and jumpers people leave behind when they die.

In solidarity for the month ahead and with unrelenting hope for a just peace in Palestine,

Tansy.

P.s. thank you for everyone who wrote lovely things about the latest Patched advice column on using skinny jeans and the mean things people say to reject and disrupt the fashion system. The next Patched will be with you in two weeks.